In obstetrics, few decisions carry the same urgency as calling for an emergency caesarean delivery.

Unlike an elective procedure, where timing can be planned and risks anticipated, emergency caesarean deliveries demand immediate action to save the lives of both mother and baby. In Malaysia, where maternal and perinatal mortality remain pressing public health concerns, the ability of obstetric teams to act swiftly and decisively can mean the difference between good and poor outcomes.

The Time-Critical Nature of Emergency Caesarean Delivery

Today, the rigid “30-minute rule” for emergency caesarean delivery is no longer the universal standard. Instead, most international guidelines now stratify emergencies by urgency: from cases where an immediate threat to the mother or baby requires delivery as quickly as possible, to less urgent categories where there is maternal or fetal compromise but no immediate danger. In reality, delays can still arise—from mobilising the team and securing anaesthesia, to preparing the theatre or transferring the patient. These challenges differ across settings: high-volume tertiary centres contend with complex cases and heavy caseloads, while district hospitals may face limitations in staffing, surgical capacity, or specialist availability.

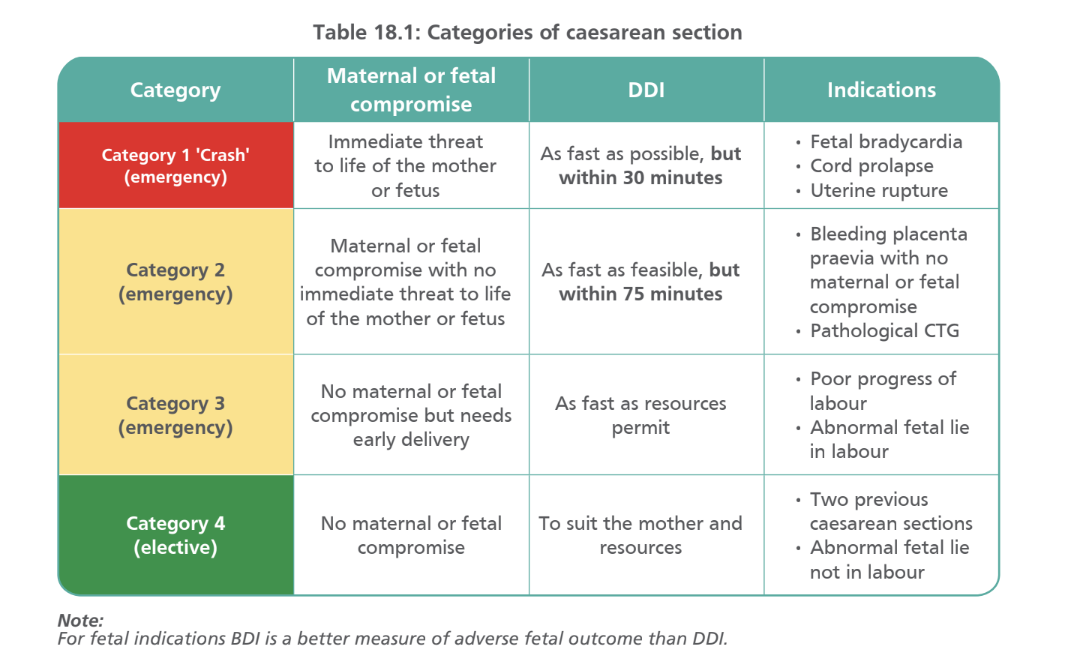

To bring structure to this urgency, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) classification, now widely adopted in Malaysian practice, defines four categories of caesarean section according to urgency.

- Category 1 (“Crash” Emergency): Immediate threat to maternal or fetal life (e.g. fetal bradycardia, cord prolapse, uterine rupture). Delivery should occur within 30 minutes, though this remains difficult to achieve consistently across many Malaysian hospitals.

- Category 2 (Urgent Emergency): Compromise without immediate threat (e.g. bleeding placenta praevia, pathological CTG). Delivery should be within 75 minutes, balancing urgency with preparation.

- Category 3 (Early Delivery): No immediate compromise, but early intervention is needed (e.g. poor progress of labour, abnormal fetal lie). Timing depends on resources and clinical judgement.

- Category 4 (Elective): Planned procedures with no maternal or fetal compromise (e.g. repeat caesareans, abnormal fetal lie not in labour).

For clinicians, the DDI reflects system efficiency, communication, and readiness. While Category 1 requires near-instant action, even Category 2 or 3 cases can escalate suddenly if vigilance lapses.

Maternal Risk Factors and Common Indications in Malaysian Practice

Emergency caesarean births are rarely random events; most are the result of risk factors that increase the likelihood of maternal or fetal compromise during labour. In Malaysian medical settings, several maternal characteristics have been consistently linked to higher emergency caesarean delivery rates, and understanding these can sharpen antenatal risk stratification.

Women with advanced maternal age face higher risks of obstetric complications, including fetal distress and poor labour progress. Obesity, gestational diabetes, and hypertensive disorders all heighten the risk of prolonged or obstructed labour, failed induction, and complications that often necessitate urgent intervention.

Against this backdrop, the most common indications for emergency caesarean deliveries in Malaysian practice include:

- Fetal distress, often presenting as non-reassuring cardiotocography or meconium-stained liquor, accounts for a large proportion of emergency operative deliveries.

- Obstructed labour, still a significant concern in both primigravida and multiparous women, particularly where cephalopelvic disproportion or malpresentation occurs.

- Placental complications, such as placenta praevia and abruptio placentae, which, though less frequent, carry high morbidity and demand rapid surgical response.

Clinical Challenges OB/Gyns Face

While caesarean rates in Malaysia have risen steadily over the past decade, this has not translated into uniform preparedness for emergencies. Resource limitations persist, especially in district hospital settings/private maternity homes, where equipment or trained personnel may be stretched thin. Even in well-staffed hospitals, communication gaps within multidisciplinary teams, between obstetricians, anaesthetists, paediatricians, and nurses, can delay the sequence of steps needed for a safe and timely delivery.

Training for Precision Under Pressure

In obstetric emergencies, knowledge alone is insufficient. A team may understand the steps of an emergency caesarean in theory, yet falter when faced with the stress and unpredictability of real cases. Hands-on drills and simulations are therefore essential to build not just technical proficiency, but also communication, coordination, and confidence under pressure.

ICOE faces this head-on through structured simulations, where obstetric teams rehearse the full chain of actions under realistic time constraints. These exercises condition instinctive responses, ensuring that when the real emergency strikes, every member of the team knows their role and can act without hesitation.

What makes simulation particularly powerful is its ability to expose participants to a range of emergency scenarios, from sudden fetal bradycardia to unanticipated haemorrhage or failed induction. By rehearsing multiple situations under time pressure, clinicians learn to anticipate complications and adjust their decision-making on the spot. Stress testing these skills in a safe environment builds confidence, sharpens clinical judgment, and ensures that when the unexpected occurs, the response is swift and decisive.

Beyond technique, simulation also cultivates psychological readiness. Recreating the intensity of real emergencies pushes participants to practise decision-making under pressure, learning how to manage adrenaline, prioritise tasks, and stay focused even when the unexpected occurs. This resilience is often the difference between a team that hesitates and one that acts with speed and precision.

Ultimately, ICOE’s approach goes beyond teaching how to perform a caesarean. It equips teams to perform together, under pressure, with confidence. It is this collective preparedness that translates into safer, faster, and more effective care for mothers and babies across Malaysia.