The birth seems routine. The head is delivered, the team exhales…and then progress stops. The baby’s shoulders are lodged, and within moments, the delivery room shifts from calm to crisis.

For the unprepared, this is a paralysing scenario. For the trained, it is a call to action: manoeuvres, communication, and teamwork moving in quick succession to prevent harm. This is what shoulder dystocia looks like—uncommon, unpredictable, but one of the most critical obstetric emergencies that every doctor and midwife must be ready to face.

Shoulder dystocia is an unpredictable obstetric emergency that requires rapid, coordinated team action to prevent hypoxia-related neonatal harm and maternal morbidity. Globally, it complicates roughly 0.15–1.7% of vaginal births, with risk rising steeply with fetal size (about 5–7% in neonates 4.0–4.5 kg).

In Malaysia, the National Obstetrics Registry (NOR) data show that the probability of shoulder dystocia increases with birthweight in Malaysian hospitals. To put this into context, in 2017, nearly 40% of babies born with a birthweight between 3.5–3.9 kg had an occurrence of shoulder dystocia at birth. Malaysia’s Perinatal Care Manual (4th ed., released May 2023) identifies shoulder dystocia as an obstetric “Red Alert” and provides a national management algorithm aligned with the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG).

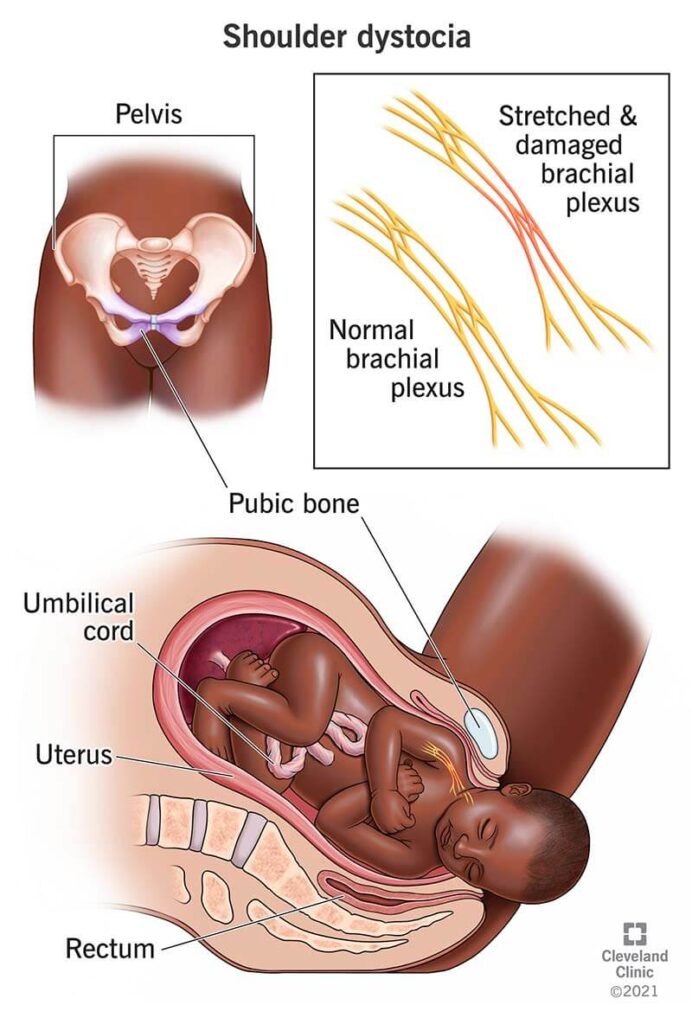

Behind these figures are stories of mothers who experience heavy bleeding, or newborns who face fractured clavicles, brachial plexus injuries, or worse, hypoxic brain injury if the shoulders remain stuck too long.

And with gestational diabetes affecting 27.1% of Malaysian pregnancies (as of 2022), the prevalence of larger babies—and with them, the risk of shoulder dystocia—remains a pressing issue.

Doctors are taught to look out for the classic warning signs: maternal diabetes or gestational diabetes, obesity, previous shoulder dystocia, a history of large babies, prolonged labour, or assisted vaginal birth. These are the textbook red flags, and in Malaysia, registry data shows that high BMI and diabetes do account for a significant share of cases.

Yet the reality is that shoulder dystocia often strikes without them. Many mothers who experience it have none of these risks, and many babies are of normal size. This unpredictability is what makes shoulder dystocia uniquely dangerous. It resists neat prediction, which is what makes it even more crucial to be trained and prepared for handling it as a high-risk birth emergency.

When shoulder dystocia is recognised, time is oxygen—literally. The baby’s head is delivered, but the chest is compressed within the birth canal, and every minute of delay increases the risk of hypoxia. The key is to follow a structured, rehearsed sequence:

- Call for help: Escalate immediately. Note the time of occurrence. Delegate someone to document the timing of each step. A shoulder dystocia is never a “one-person” emergency. Clear role allocation – who leads, who performs manoeuvres, who monitors time – is vital.

- McRoberts’ manoeuvre: Simple, fast, and often effective. The mother’s legs are hyperflexed tightly onto her abdomen, rotating the pelvis and straightening the sacrum. This increases the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis, freeing the impacted shoulder.

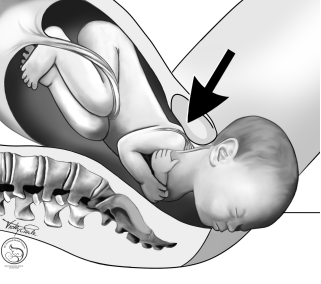

- Suprapubic pressure: Applied with the palm or heel of the hand just above the maternal pubic bone, directed obliquely downwards and laterally towards the fetal chest. The aim is to push the anterior shoulder into a more oblique position and dislodge it from behind the symphysis. NEVER apply fundal pressure; it risks driving the shoulder tighter into the pelvis and increases the chance of injury.

- Internal Manoeuvres. If external measures fail, the next step is to enter the vagina. Options include:

○ Rotational Manoeuvres like the Rubin or Woods’ screw manoeuvre

○ Delivery of the posterior arm: sweeping the posterior arm across the chest and out, reducing the shoulder diameter and allowing descent. This is often the most effective internal manoeuvre when done early. - Change of maternal position. If rotation fails, moving the mother onto all fours (the Gaskin manoeuvre) can alter pelvic dimensions and facilitate delivery.

Each manoeuvre is designed to create more space, rotate the shoulders, or reduce the fetal diameter. The sequence is less important than the principle: move quickly, escalate stepwise, and communicate clearly.

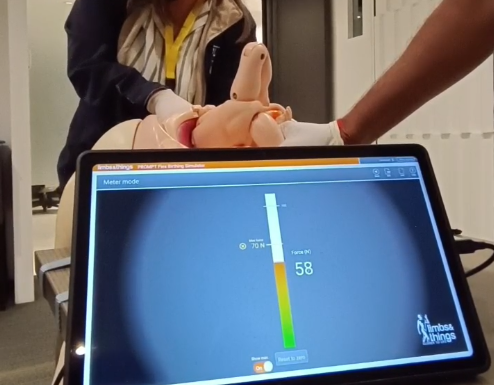

No matter how many lectures a clinician attends, nothing compares to hands-on simulation. Studies from the UK’s PROMPT training programme show that regular drills reduce brachial plexus injuries and achieve a 100% reduction in permanent brachial plexus injuries after shoulder dystocia.

In Malaysia, where many obstetric units face high delivery loads and limited staffing, the ICOE programme is designed with these realities in mind. Its philosophy is simple: build muscle memory before the crisis.

Training scenarios mirror the pressures of a busy labour ward, where quick role allocation, clear communication, and meticulous documentation can make the difference between a smooth resolution and a devastating outcome. By practising shoulder dystocia drills repeatedly in teams, Malaysian doctors and midwives step into real emergencies not with hesitation, but with rehearsed confidence, turning potential chaos into coordinated care.