In the steep, winding trails of Nepal’s highlands, where roads vanish into the mountains and mobile signals waver like smoke, childbirth is a celebration, but one wrong turn and it becomes a crisis in the making. Here, where the nearest health post can be a three-day walk away, obstetricians, nurses, and midwives must navigate life-or-death scenarios without the safety nets their urban counterparts take for granted. And yet, every day, they show up. Improvising. Adapting. Delivering.

Nepal’s maternal healthcare system has made strides in recent years, but the contrast between its cities and remote regions remains stark. In urban centres like Kathmandu or Pokhara, a woman in labour has access to full obstetric care. In places like Mugu or Dolpa, however, getting to a hospital often requires navigating treacherous paths on foot or being carried in a wicker basket across rivers and ravines. Sometimes, the journey is too long, and the baby arrives before the help does.

Improvisation is Second Nature

In these circumstances, healthcare workers are often forced to work with what they have, which, more often than not, is very little. One of the most pressing concerns is postpartum haemorrhage—a leading cause of maternal death in Nepal. In hospitals, this would be treated with a uterine balloon tamponade (UBT), a medical device designed to stop the bleeding. In rural Nepal, midwives have been trained to create makeshift UBTs using a condom, a catheter, and a syringe. It’s not ideal, but in the absence of better tools, it saves lives.

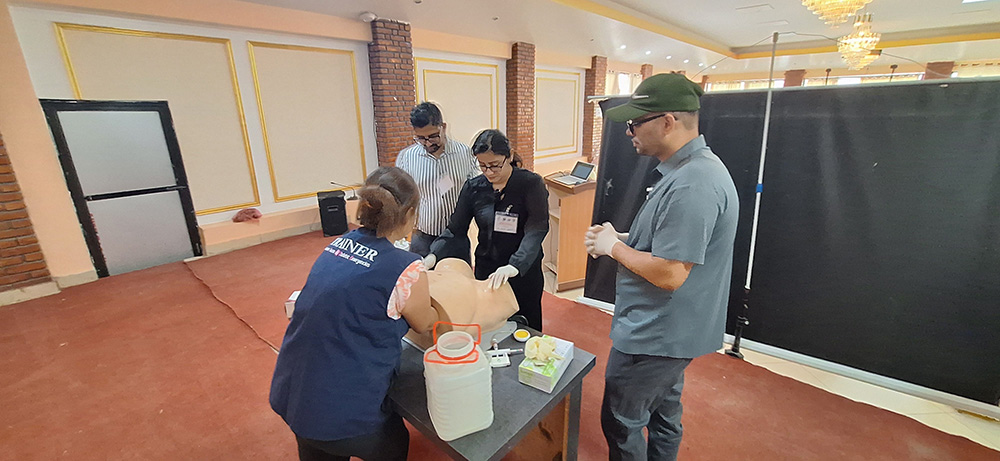

This kind of improvisation is not unusual. At many remote outposts, simulation tools used in obstetric emergency training, like birthing mannequins, are either unavailable or unaffordable. Instead, midwives and trainees practise on cardboard pelvises and cloth dolls, relying on their imagination and muscle memory. At one facility, nurses used empty plastic bottles to simulate the uterus during drills. These tools are a far cry from modern simulation labs, but they provide a chance to prepare for the worst.

The Efforts to Do Better

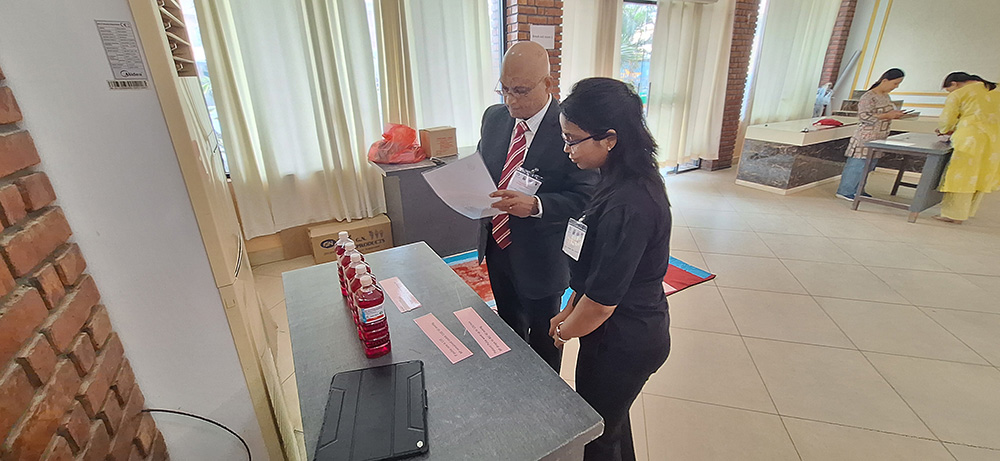

This year, as the ICOE team made their way to Butwal for a training session in April, these skills were central to a workshop, supported by the Asia & Oceania Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (AOFOG) and the Nepal Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (NESOG). The aim: to equip OB-GYN doctors from across the region with the skills to manage high-risk obstetric cases using whatever tools and knowledge they could access.

Improvisation is only one part of the story. The government and international NGOs have introduced initiatives to equip frontline workers with the skills they need. For instance, the Advanced Skilled Birth Attendant (ASBA) programme has enabled midwives and nurses to perform emergency procedures traditionally reserved for doctors.

More Problems Than Meet The Eye

Despite these efforts, gaps remain. Access to basic equipment continues to be inconsistent. In some mountainous regions, portable ultrasound machines are delivered too infrequently to detect complications in time. Referral systems are weak or nonexistent. Ambulances can’t navigate the terrain. Telemedicine, while promising, is still limited by connectivity issues and infrastructure gaps.

There are also structural issues. Although hundreds of new midwives graduate yearly, not all are absorbed into the public healthcare system. Many end up leaving the country or shifting to better-paying jobs in urban centres. For those who do remain, isolation can take its toll. Without regular training refreshers or mentoring, skills deteriorate. A 2019 study noted that up to 80% of rural birth attendants lacked up-to-date knowledge on managing obstetric emergencies.

Cultural practices also shape how and where women give birth. In some remote communities, childbirth is seen as a private, even impure, event that should occur in seclusion. This stigma discourages women from seeking medical help, even when complications arise. Community-based interventions, such as women’s participatory groups, have shown promise. When women are empowered to discuss maternal health in safe, local forums, outcomes improve. In districts where participation exceeded 30%, maternal and newborn deaths dropped by over a third.

Training and Resilience Always Come to The Rescue

Still, stories of resilience shine through. In Karnali Province, nurse Samjhana Salami travels from village to village with a portable ultrasound in her backpack. Her presence has helped reduce home births to nearly zero in her region. In a small fistula clinic supported by UNFPA, women once abandoned after traumatic childbirth injuries are treated and rehabilitated, often returning to advocate for safer birthing practices in their communities.

Reflecting on the experiences of these healthcare workers, one message stands out: emergency training saves lives. Improvised solutions are powerful, but only when applied correctly and confidently.

Training that incorporates low-cost simulation tools, scenario-based drills, and periodic refreshers can help frontline workers build the muscle memory they need in high-stakes situations. Programmes like ICOE, which focus on practical, hands-on training, are especially valuable. Embedding such courses within national health systems and ensuring ongoing mentorship, can prepare Nepal’s rural clinicians better, not just to improvise, but to excel.

As Nepal continues its journey toward safer motherhood, the ingenuity of its rural OB-GYNs must be met with robust support. With the right training, resources, and policy focus, these doctors and midwives can stop being forced to make do and start being empowered to do more.